THE CLASSICAL 'HIS' AND 'HERS'

The classical ‘HIS’ and ‘HERS’…

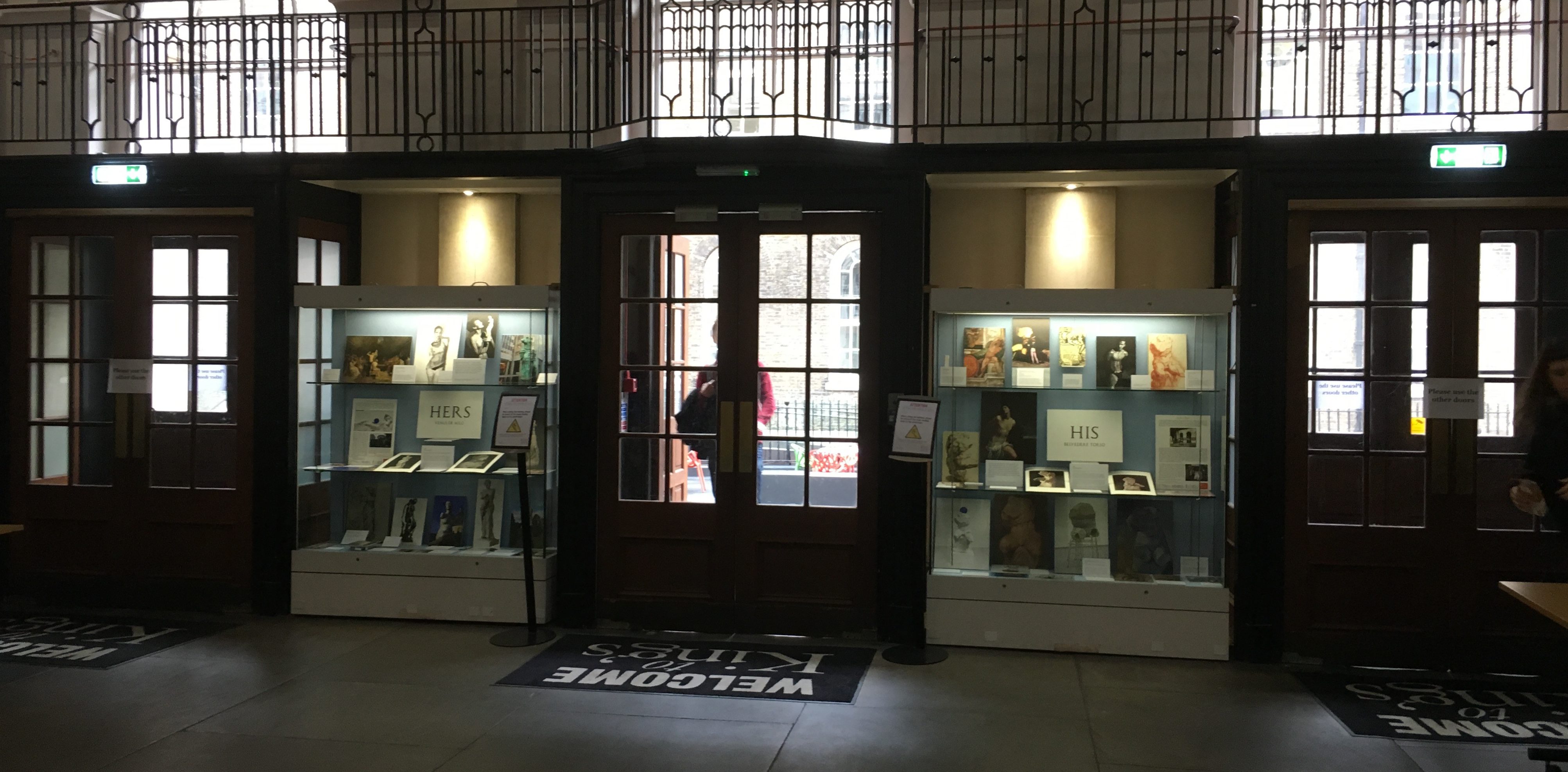

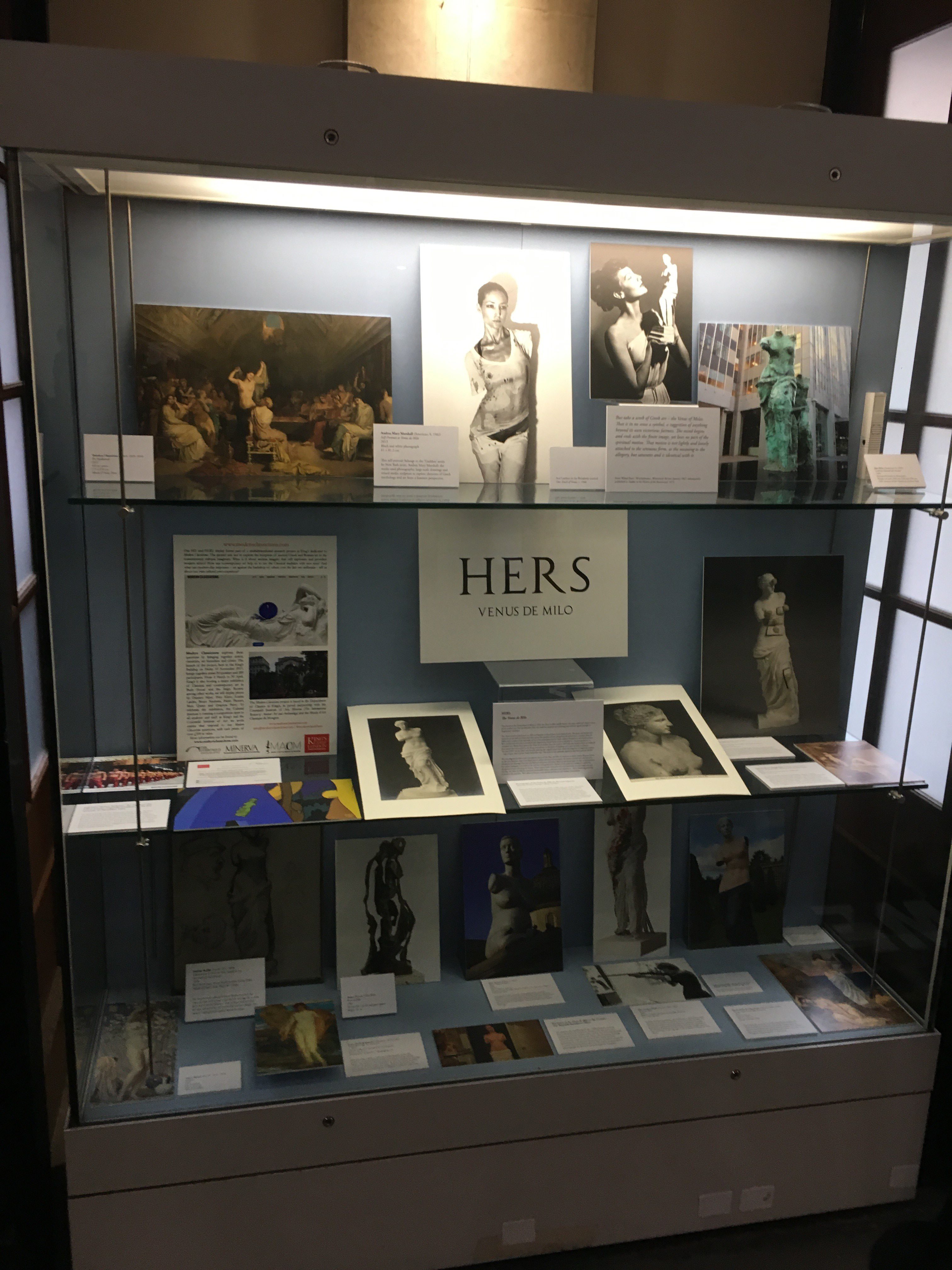

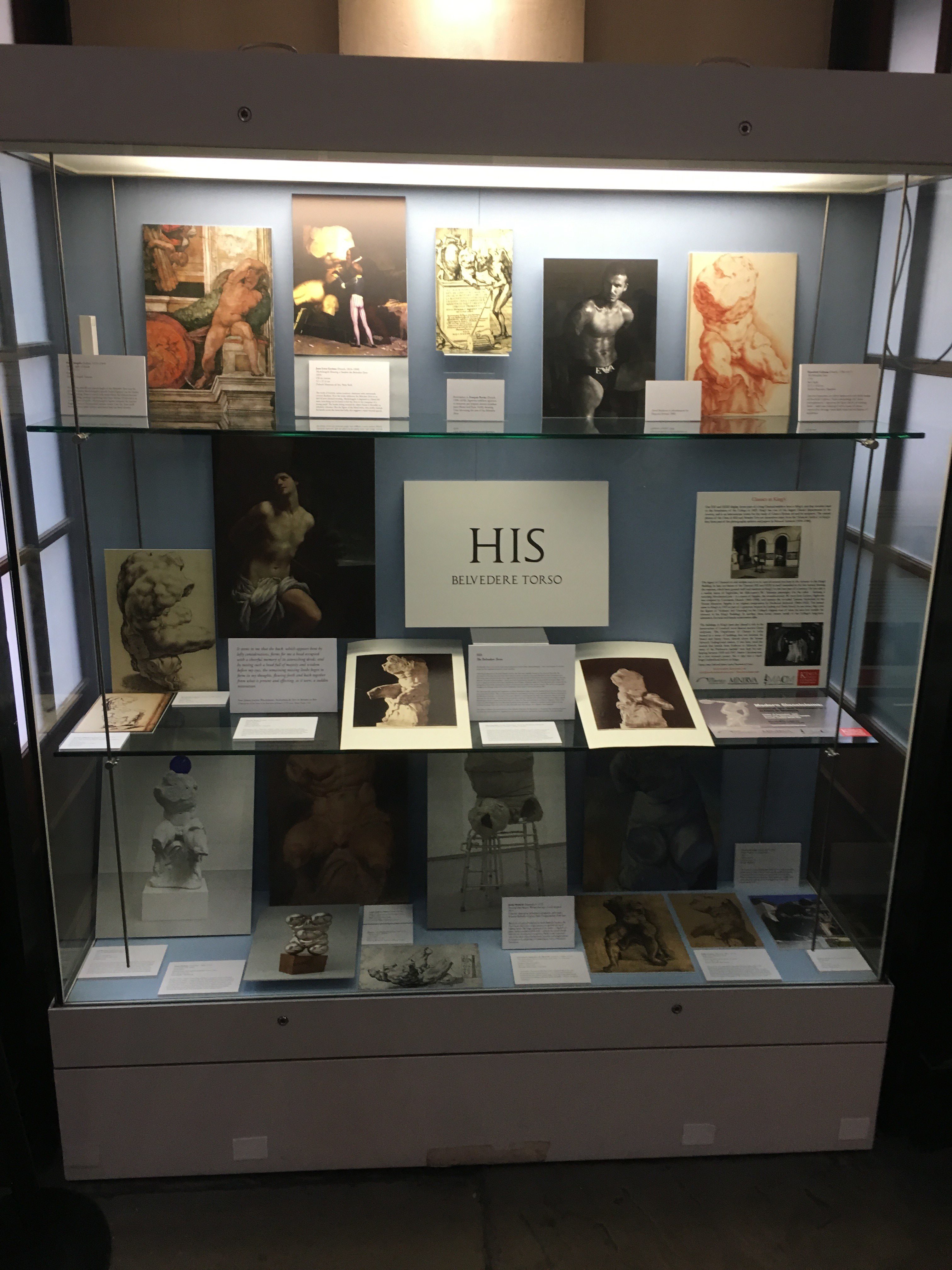

As part of our preparations for the Modern Classicisms launch on Friday 10 December, James Cahill and Michael Squire have installed a temporary exhibition in the Entrance Hall of the King’s Building. The two display cases are centred around the ‘His’ and the ‘Hers’ of classical visual traditions, and explore the afterlives of two particular ancient sculptures: one case is structured around responses to the Venus de Milo, the other around responses to the Belvedere Torso.

The themes of our two cases also chime with the classical resonances of the King’s Entrance itself, structured around two classical statues that frame the main staircase. On one side, a neoclassical statue of the fifth-century Athenian playwright, Sophocles (after the so-called ‘Lateran Sophocles’ in the Vatican Museums); on the other is a statue of Sappho, the sixth-century lyric poet from Lesbos.

The display cases also outline some of the aims and aspirations of the Modern Classicisms project, with some details about our forthcoming exhibition in spring 2018, and a bit of history about the Department of Classics at King’s.

Our display in the King’s Building will run until 1 May 2018: do come and take a look! As always, feel free to get in touch with your responses, by using the hashtag #modernclassicisms, or emailing us at info@modernclassicisms.com!

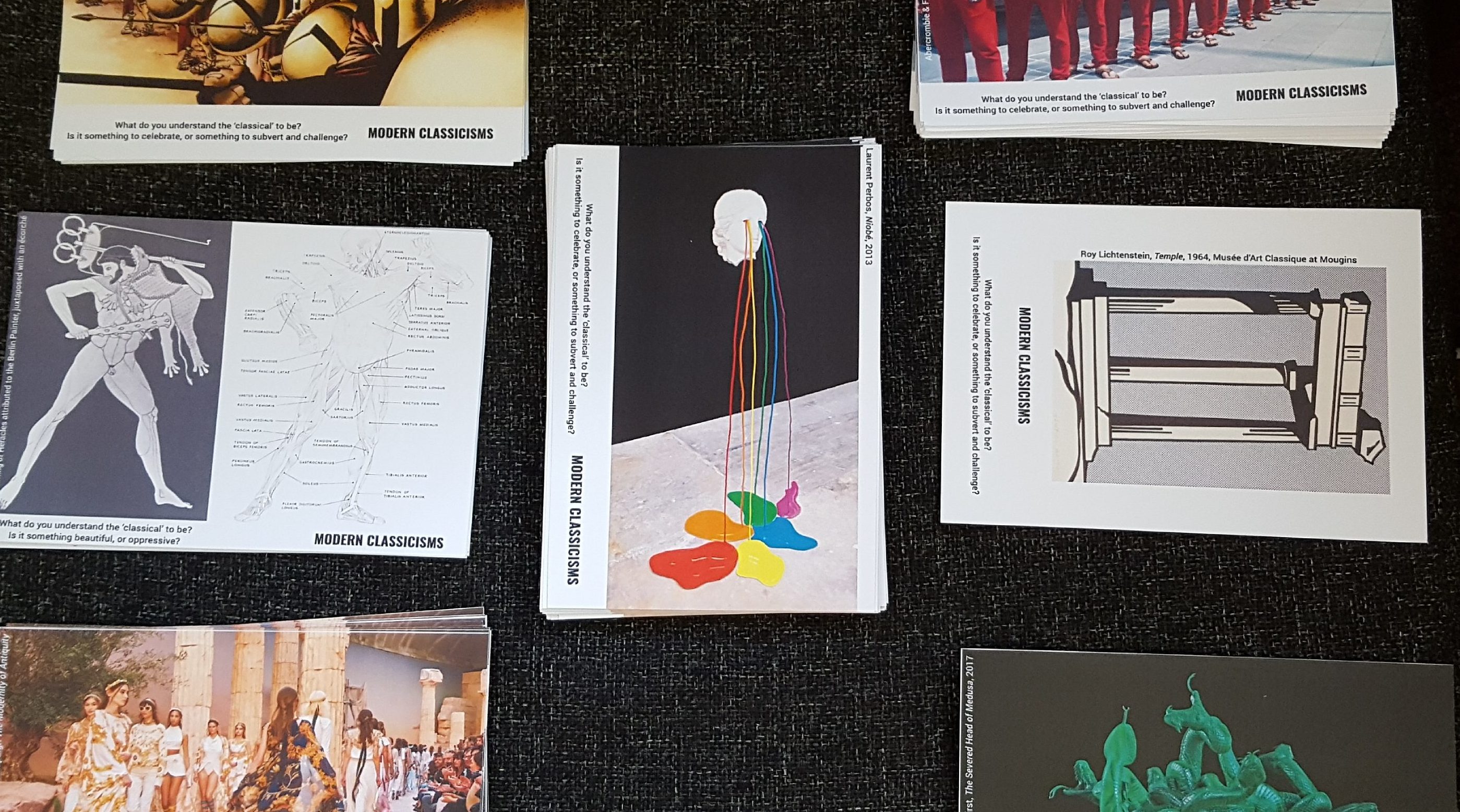

FLYERS FOR CULTURAL INSTITUTE'S STUDENT AND STAFF COMPETITION - COLLECT THE SET!

Flyers for the Cultural Institute’s Student and Staff Competition – collect the Set!

The Modern Classicisms launch is nearly upon us and, following talks from artists, writers, scholars and critics, we want to see what the theme has inspired in you. The project is therefore running a competition in partnership with the Cultural Institute at King’s.

The competition offers the opportunity for King’s College London and the Courtauld Institute of Art students and staff to showcase their own personal responses to the theme of Modern Classicisms. What does this legacy mean? What do you understand the ‘classical’ to be? Where do you see its influences? How do you respond to it? Is the classical something beautiful, or oppressive? Is it something to celebrate, or something to subvert and challenge?

Our student ambassadors have been working on flyers that will soon be gracing the KCL and Courtauld campuses, offering a variety of provocations about the Modern Classicisms theme. Drawn from fashion catwalks, through comic books to contemporary galleries and science, the flyers show how the classical is not restricted to highfalutin artistic creativity. Instead, the competition seeks to probe the diverse pool of expertise available throughout our campuses and encourage innovative responses in a variety of media, subjects and forms.

After some technical difficulties and several attempts at formatting (third time lucky!), the flyers are now – finally! – ready for their public appearance, and we will be trying to bring them to as many campuses as possible. If you are interested in the project, then do stop by for a chat about the competition or Modern Classicisms project. Indeed, if you think you are not interested, stop by for a chat anyway: you might find the classical in unexpected places.

You can also see the flyers featuring in the ‘HIS’ and ‘HERS’ display cabinets at the entrance to the King’s Building of the Strand Campus.

For more specific information on the competition and how to apply visit https://modernclassicisms.com/competition/ or email competition@modernclassicisms.com. Also don’t forget to check out our sister project at the University of Leicester, Artefact to Art.

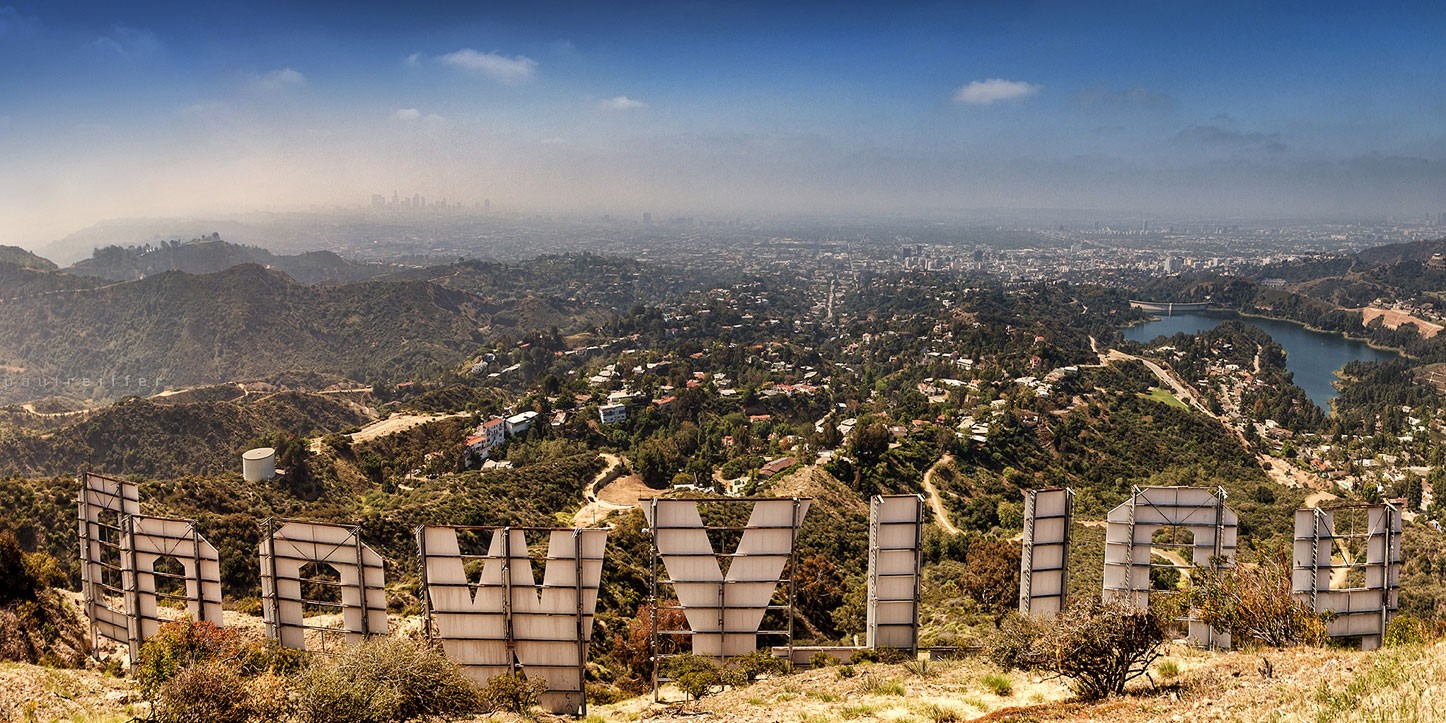

CALIFORNIAN ANTIQUITY?

Californian antiquity?

In her second blog from Los Angeles, Ruth Allen writes about a mural by John Werle and a current show on William Leavitt: Cycladic Figures…

I ended my last post on Modern Classicisms in L.A. with Adrian Villar Rojas, discussing how his Two Suns (II) (2015) gets viewers recalibrating their centre of cultural reference. The same is true of John Werle’s mural, Galileo, Jupiter, Apollo (1983), which mixes references to classical myth, Spanish history and planetary exploration. Decorating a section of the 1984 Olympic Freeway, the painting depicts fragments of classical sculpture – including the central Apollo from the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and the seated Dionysus from the east pediment of the Parthenon in Athens – suspended in space. The planet Jupiter looms in the background, while the satellite, Galileo, hovers to the left; a floating astronaut reaches towards a disembodied marble hand in a riff on Michelangelo’s depiction of Adam and God from the Sistine Chapel. Classical art – and perhaps all Western European history – has seemingly been blown away in favour of the space-race and the quest for modernity.

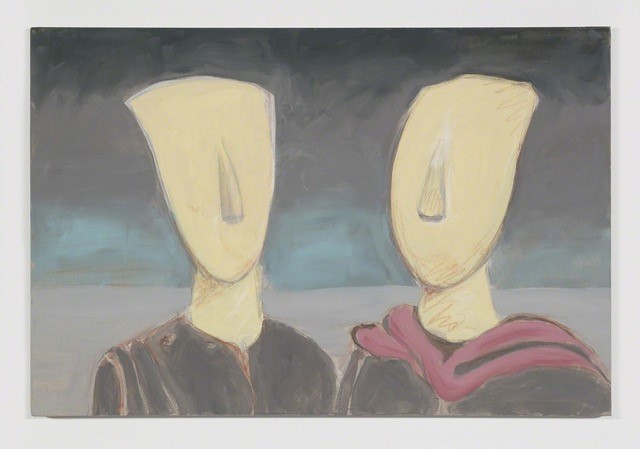

Another recent favourite show of mine has been Honor Fraser’s current exhibition, William Leavitt: Cycladic Figures. In the painting illustrated below the artist uses the motif of two Cycladic heads posed as if in conversation to explore multiplicity, storytelling and history-making. Repeated across a series of paintings, sometimes as ‘portraits’ of dressed figures, sometimes as silhouettes that form their own picture planes, filled with images of landscapes, urban settings, or architectural remains, Leavitt uses the blank space of the Cycladic heads to suggest that identity might have less to do with our exterior appearance, and more to do with our inner thoughts and imagination.

As so often in L.A., the classical is here. But in this most self-consciously modern of American cities, it is often evoked in subtle, playful and unexpected ways.

5–4–3–2–1… COUNTDOWN TO OUR OFFICIAL LAUNCH ON FRIDAY 10 NOVEMBER!

5–4–3–2–1… Countdown to our official launch on Friday 10 November!

The King’s Building display cases are installed, the delegate packs have been packed, and speakers from around the world are beginning to arrive in London: everything is in place for our Modern Classicisms launch event on Friday 10 November here at King’s!

The launch explores the theme of ‘Classical Art and Contemporary Artists in Dialogue’, and has been organised in partnership with the Arts and Humanities Research Institute at King’s College London, the Courtauld Institute of Art, Minerva (The International Review of Ancient Art and Archaeology) and the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins.

In total, 35 artists, academics, journalists and critics will be speaking, and our final programme can be viewed here. Our speakers and panelists are: Ruth Allen, Tiphaine Annabelle Besnard, Bruce Boucher, James Cahill, Léo Caillard, Sir Michael Craig Martin, Lindsay Fulcher, Russell Goulbourne, Donatien Grau,Constanze Güthenke, Patrick Kelly, Charlotte Higgins, Brooke Holmes, Nick Hornby, Jessica Hughes, Patrick Kelley, Polina Kosmadaki, Christopher Le Brun, Christian Levett, Jo Malt, Simon Martin, Ursula Mayer, Bénédicte Montaine, Minna Moore Ede, Robin Osborne, Christodoulos Panayiotou, Leisa Paoli, Elizabeth Prettejohn, Marc Quinn, Mary Reid Kelley, Alexandre Singh, Michael Squire, Caroline Vout, Evelyn Welch, Sarah Wilson and Raphael Woolf.

We are expecting a full house: we were able to release around 250 tickets for the day, and there is now a long waiting list.

If you wanted to join us, but were unable to get a ticket, please do come back to our website soon: a team will be filming the day, and we will be making a short documentary later in November.

'MODERN CLASSICISMS' IN L.A.

Modern Classicisms in L.A.

Ruth Allen (Post-Doctoral Fellow in Modern Classicisms) posts about some of the latest Graeco-Roman resonances in Los Angeles…

Los Angeles is an unusual city in which to look for contemporary takes on classical art. It is far more concerned with the ‘now’ than with the ‘then’, its art and architecture more influenced by Spanish Colonialism, twentieth-century Modernism, and heavy industry than by European neoclassicism, more likely to look to the pre-Hispanic cultures of Latin America than to ancient Greece and Rome. And yet the classical is here, often evoked in playful and unexpected ways. During my time as a curatorial intern at the Getty Villa (from September 2017), I have been enjoying tracing its presence around the city. Here are just two of my current favourites – with two more to follow in a separate post.

Standing on the stairs at the Getty Center’s main entrance, Charles Ray’s Boy with Frog (2009) is a larger-than-lifesize painted fiberglass sculpture of a nude boy grasping a frog in one outstretched hand. The nudity, subject and pose all refer to the Apollo Sauroktonos, a famous Greek bronze, attributed to Praxiteles, that depicts the youthful god Apollo teasing a lizard with one of his arrows; the pristine white finish also recalls the appearance of classical marble. However, Ray’s engagement with his ancient model suggests ambivalence towards its perceived status as an icon of classical – and Western – art: the languid, seductive body of the original has been replaced with the awkward limbs of a pre-pubescent boy, the god’s divine indifference with impish malice, marble with fiberglass and steel. Even the lizard’s transformation into a warty frog pokes fun at Praxiteles’ sculpture: the original iconography perhaps alluded to Apollo’s conquest of the Python, here it is nothing more than a boy playing games.

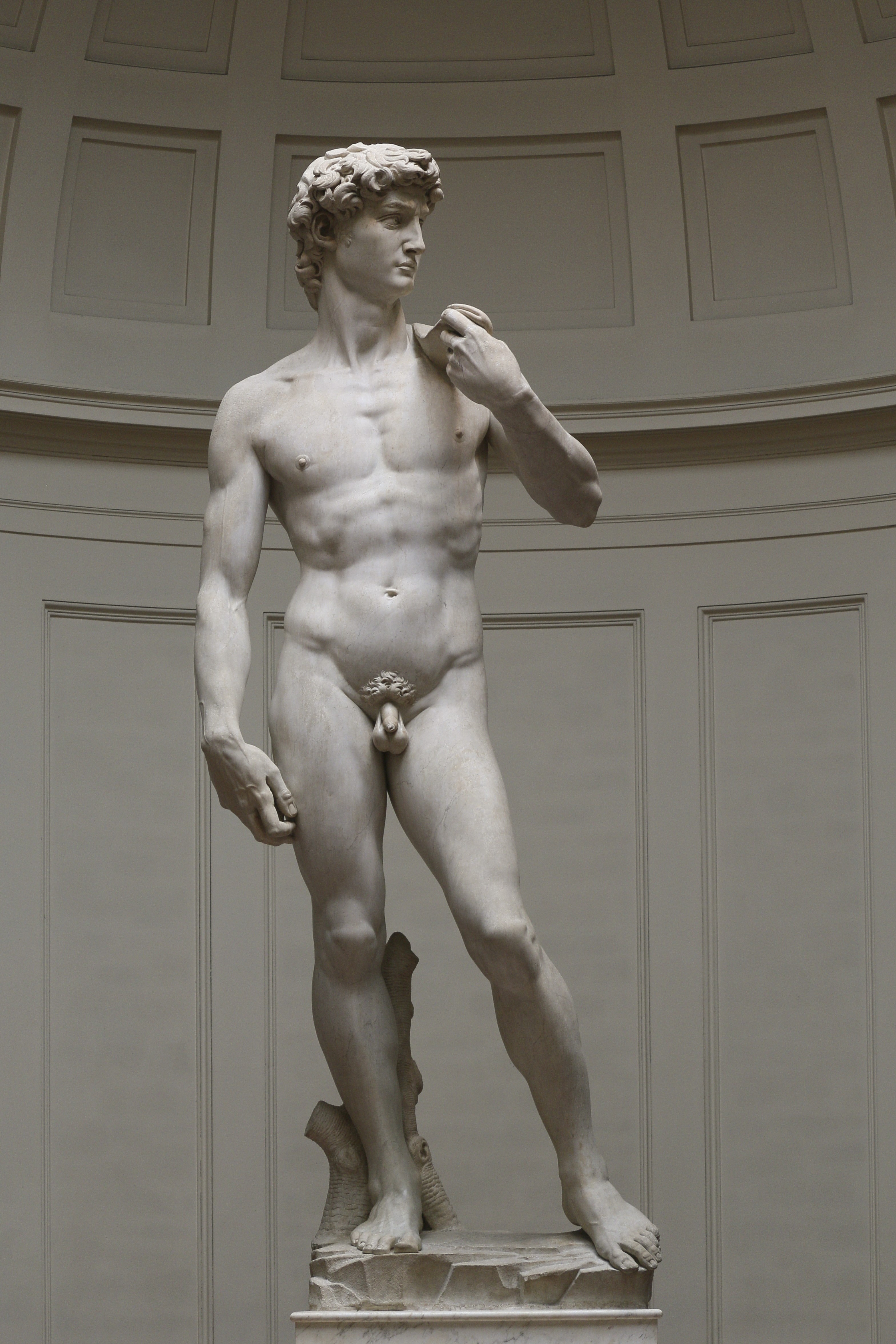

At the city’s newest contemporary art museum, the Marciano Art Foundation, Adrian Villar Rojas’ current site-specific installation, Two Suns (II) (2015), presents a different ‘classical’ nude. Turned on its side, a seventeen-foot replica of Michelangelo’s David is laid out on two supports, floating above a cement floor embedded with detritus, including seashells, bike tyres and drinks cans. With his eyes closed and head buried in his arm, it is unclear whether this David is asleep or has in fact been defeated by Goliath. The sculpture is cracked and worn, and is presented as an archaeological discovery, or an anatomical specimen for dissection. As ruin, Rojas’s installation consequently undermines the dominance of Western art and culture in traditional art historical narratives, asking us to recalibrate our centre of reference.

A MONTH IN MOUGINS

A Month in Mougins

During the summer of 2017, I was lucky enough to spend a month on an internship at the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins in southeast France. This formed part of a larger initiative set up by the Department of Classics last year, thanks to the support of the EU Erasmus+ scheme and the Study Abroad programme at King’s. I was one of two Modern Classicisms student ambassadors to spend the summer in Mougins: Belinda Martin Porras was able to spend two months on a similar internship in 2017.

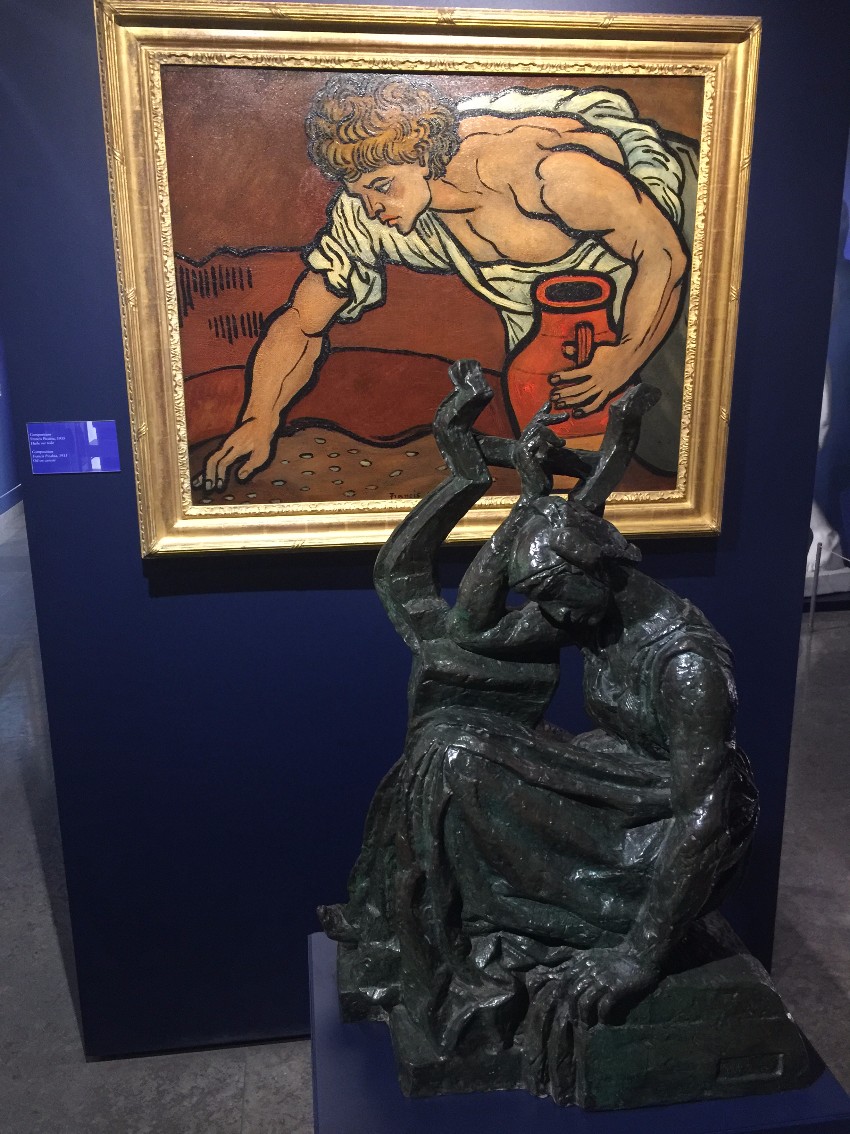

Perched on the top of the picturesque village of Mougins, overlooking the Côte d’Azur, the museum is unique for championing the display of ancient art alongside its modern and contemporary descendants. There are very few places in the world where you get to see such juxtapositions: a 1950s Chagall alongside an Egyptian stone bust dating to 1000 BC, for example; Damien Hirst’s 2007 Happy Head alongside a first-century A.D. bronze head of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus; Grayson Perry’s 1989 A Classical Compromise surrounded by fifth- and fourth-century B.C. Greek pottery vessels. The name-dropping is impressive to say the least.

I could easily wax lyrical about the internship’s importance as work experience: learning the inner-workings of a museum like the one at Mougins first-hand was invaluable, especially as I now embark on my PhD (and considering a career in the culture and heritage industries). But when it comes down to it, what could be better than spending a month working with masterpieces of the ancient and modern tradition, curated in such a rich narrative? More to the point, the summer was spent in the company not only of artistic masterpieces, but also of a curatorial team who are so passionate about what they do.

I cannot wait to see so many highlights from the collection again in the spring 2018 exhibition at King’s. The Museum is also heavily involved in our launch event on 10th November 2017.

Abigail Walker (first-year PhD student, Department of Classics, King’s College London)

ONE MONTH LEFT TO ENTER ‘ARTEFACT TO ART’ COMPETITION...

Just one month left to enter the ‘Artefact to Art’ competition…

Our sister project, Artefact to Art, has launched a national competition – open to different age categories: there are just four weeks left until the competition closes.

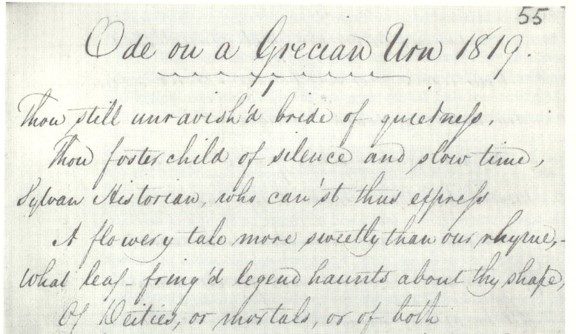

The initiative is run by the University of Leicester and the Classical Association, and the competition is for works of visual art or poetry inspired by ancient artefacts. Winning entries will receive book tokens; selected entries will also be published in a specially-commissioned book, as well as be displayed during the Classical Association Annual Conference in Leicester (6th–9th April 2018). If the ancient world inspires you, or you want to inspire younger audiences in turn, do be sure to share your entries with the Artefact to Art team!

Students and staff at King’s and the Courtauld Institute are also reminded of our London competition: details can be found here.

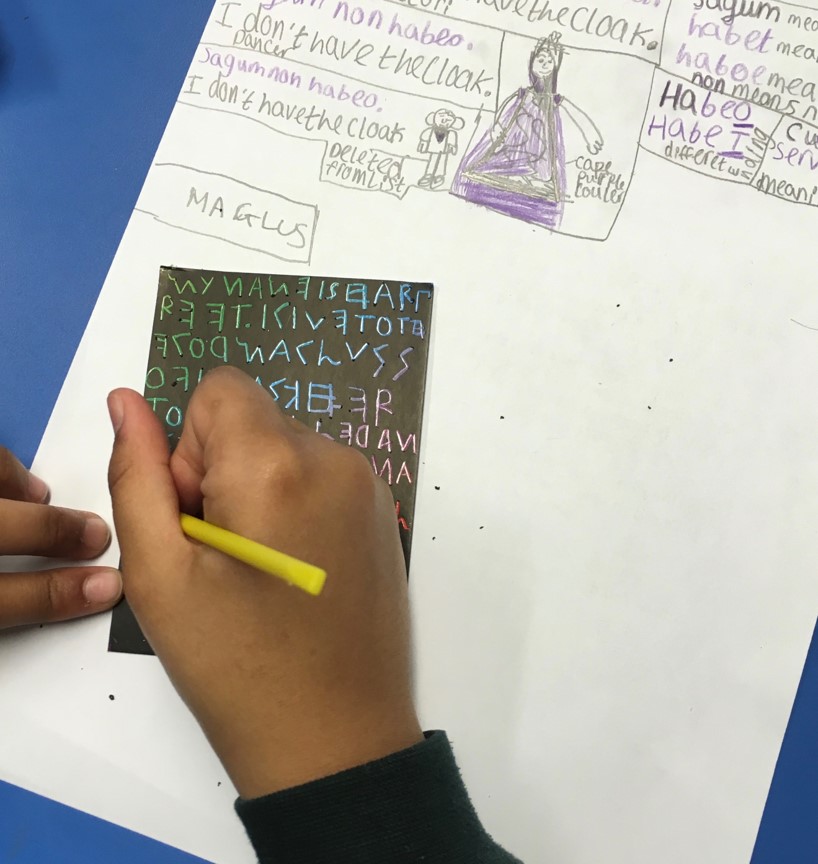

The ‘Artefact to Art’ programme also runs schools workshops and is particularly keen to receive competition entries in the age categories ‘Under 11’, and ’11-18’.

Competition deadline: 25th November 2017.

For more details, visit: http://www.artefact-to-art.com/competition.html, or email artefact2art@le.ac.uk.

THE THONG OF DIONYSUS

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: The Thong of Dionysus

As part of the Modern Classicisms workshop on 10 November, we will screen Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s The Thong of Dionysus – the first presentation of the film in the UK. The New York-based artists have earned wide acclaim for their surrealist and darkly comic reimagining of ancient myths. Their films relate (and corrupt) ancient tales into cartoonish psychodramas, accompanied by pun-laden narratives. In this film, Dionysus and three maenads discourse on the nature of drunkenness, while propositioning Ariadne to join them on the island of Naxos.

‘Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: We Are Ghosts’ – the artists’ first solo exhibition in the UK – opens at Tate Liverpool on 17 November.

The screening on 10 November at King’s will be followed by an interview with Mary and Patrick.

A JOURNEY INTO THE UNBELIEVABLE

A journey into the unbelievable: James Cahill describes Damien Hirst’s Venice extravaganza.

This summer marked the unveiling of Damien Hirst’s Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, a gargantuan exhibition ten years in the making. Spread across the two vast sites of the François Pinault Foundation in Venice – an eighteenth-century palazzo and a former customs house – Hirst’s show is a sumptuous, hyperbolic journey through ancient myth and fake history.

The arrayed ‘treasures’ include bronze and marble sculptures of various scales, and myriad artefacts in gold, silver, malachite, jade and other rarefied media. At the core of Hirst’s imaginary museum is the headless bronze-painted Demon with Bowl, which rises eighteen feet through the central atrium of the Palazzo Grassi – a kind of Colossus-of-Rhodes-meets-Gothic-horror-story. The show comes with a suitably fanciful backstory – the treasures are said to be the collection of wealthy freedman, Amotan II, who lived in the first century AD, and who collected voraciously from every corner of the ancient world.

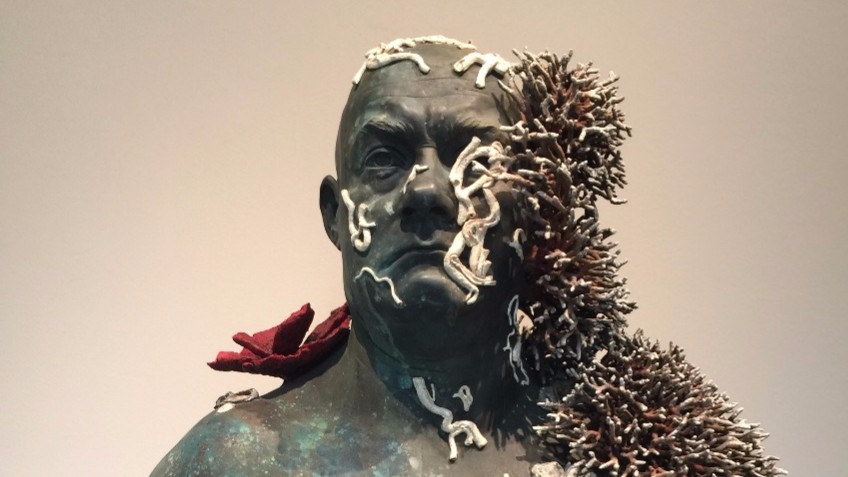

Many of the exhibits are encrusted with marine life. But the story is – of course – a mythic mirage. Unreality – or unbelievability – is the point here. A bronze statue of the metamorphosing Arachne, part caryatid and part spider, stands before a lunette window facing the canal. When I visited, a yacht called ‘Dream’ happened to be floating past – it might almost have been part of Hirst’s dizzying mythosphere.

The exhibition runs until 3 December.

TRIP TO THE MUSEUM OF CLASSICAL ART AT MOUGINS

July 2017 saw a two-day research trip by the Modern Classicisms team to the Museum of Classical Art at Mougins: the world-class collection of ancient and modern art will be at the core of the Modern Classicisms exhibition at Bush House next year.

Christian Levett (owner of the Museum) and Leisa Paoli (Director) gave us a personal tour of the galleries. The museum opened a decade ago and houses a stunning collection of ancient statuary, vases, armour, coins and jewellery, displayed alongside paintings and sculptures from later centuries. The museum is housed in a mediaeval residence; it is filled with some 700 objects, in which ideas of the ‘classical’ are variously embodied or challenged.

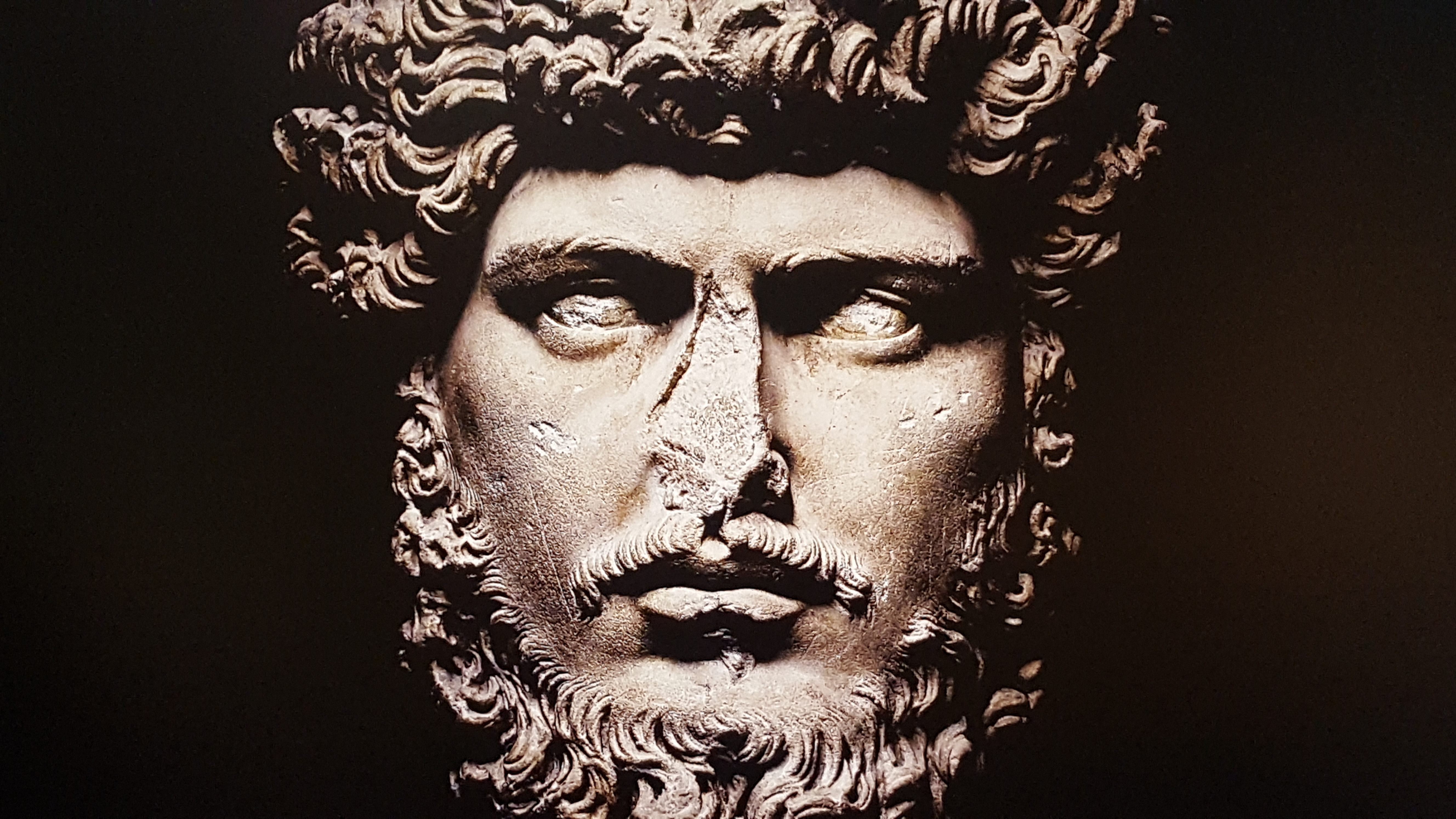

Spanning four floors, the collections encompass Egyptian treasures (installed in a crypt-like subterranean space), Greco-Roman antiquities (including a hulking, scarred Antinous retrieved from the sea), an armory of ancient battle-wear, and modern and contemporary artworks which respond – in diverse ways – to the sculptural bodies, mythological themes and historical events of antiquity.

Mougins is a tranquil hilltop town on the heights of Cannes. It became a favoured haunt of leading twentieth-century artists including Pablo Picasso (who spent his final years there), Jean Cocteau, Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and Arman. These and many others are represented in the museum’s displays. Ancient and modern objects sit side-by-side in original, witty and often provocative juxtapositions. Amid the collection of bronze armour is a photograph by Man Ray of an antique ‘metal helmet’ – the ancient object visualized as a piece of Modernist sculpture. Among a group of ancient busts of civic and divine characters is a sugar-white marble sculpture by Marc Quinn depicting a blind subject. The sensual and surreal scenes of Picasso’s Vollard Suite etchings of the 1930s find echoes, meanwhile, in the ancient erotic amulets lining one of the staircases, including a monumental marble phallus.

One of the museum’s highlights is a cabinet of Venuses, in which different incarnations of the ancient goddess – Yves Klein’s Blue Venus, Warhol’s psychedelic version of Botticelli, a Roman torso, and Salvador Dalí’s elongated Vénus à la girafe – jostle for position. Outside on the balcony, overlooking the hills and forests (ablaze, in parts, from summer fires), two male figures square up in similar fashion: Antony Gormley’s symmetrical bronze Reflections are modern variants upon the ancient form of the kouros or male votive figure, which also evoke the myth of Narcissus, entranced by his own reflection.

The King’s team hugely look forward to bringing a selection of these treasures to Bush House in spring 2018.