THE FUTURE OF ANTIQUITIES?

The future of antiquities?

Michael

Squire met

with Christian Levett to discuss the history of his collection – and to ask

about his interest in ‘Modern Classicisms’…

Christian

Levett has amassed one of the world’s most important private collections of

antiquities. In 2011, he opened his own museum in southern France to house part

of the collection: the MACM (Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins).

Over the last few years, and increasingly since his retirement, Levett has

sponsored archaeological excavations, exhibitions and outreach projects – which

included The

Classical Now show at King’s College London. He is owner of Minerva, and

sits on the Board of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and on the Arms and Armour

Committee at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

MS: Christian, can you start by telling us something

about the history of your collection: what were the first things that you remember

collecting?

CL: Collecting has always been a passion of

mine. As a young boy I used to visit shops selling old coins and medals.

Whenever I could afford them, I tried to buy inexpensive items like cheaper

Victorian coins and First and Second World War campaign medals. I also loved

toy soldiers and making aeroplane models – those were the first things I remember collecting.

MS: So what led you to

antiquities specifically?

CL: I think I had always been inspired by

family visits to museums, castles and cathedrals. But it was only later that I

became interested in ancient objects. Around 20 years ago work took me to

Paris, and I often spent Sunday mornings in the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay. I

had started collecting again – above all, to furnish my apartment and

my house in London. Back then, ordering auction catalogues in my 20s, I

had always overlooked ‘antiquities’ – I thought they were restricted to places

like the Louvre, Met or British Museum. Discovering what was available on the

market was like a bolt from the blue: I had been financially successful, and I

was drawn to these amazing ancient works.

MS: Part of your collection is

now on display in southern France – at MACM (Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins).

What led you to found your own private museum?

CL: The MACM really just evolved naturally

from those early purchases. The collection became so large, and was clearly way

beyond what I could display at home in London (and, by then, a newer house in

France). I therefore decided to put the pieces on public display: I wanted them

to be available for everybody to see – members of the public, as well as

scholars.

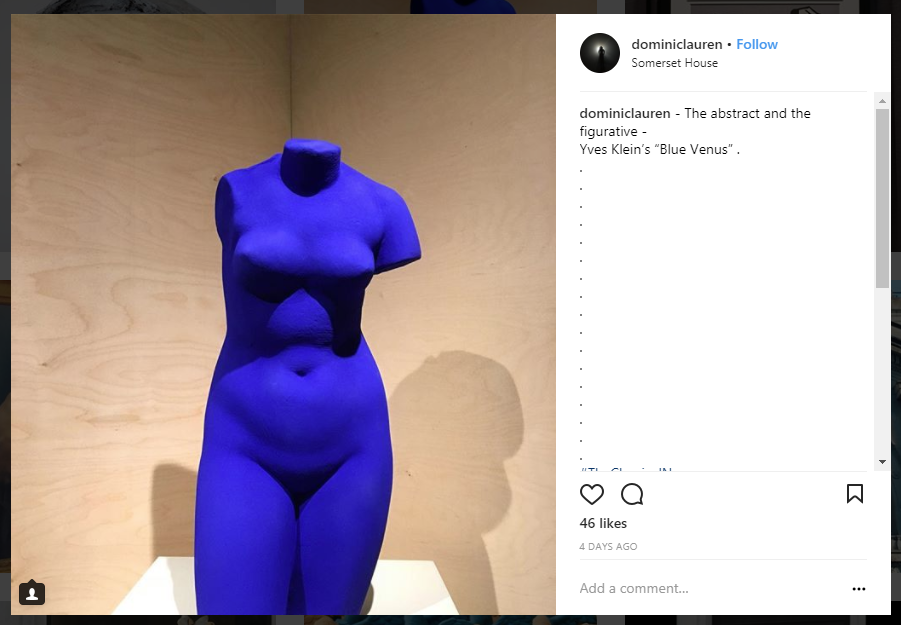

MS: What’s particularly distinctive about MACM is its

mode of display, showing ancient pieces alongside modern artworks that respond

to Graeco-Roman art. Outside the museum,

visitors to the town are greeted from below by Antony Gormley’s Reflection. Inside, we find unexpected

pairings: a Marc Quinn bust amid your Roman portraits, for example, and various

‘Venuses’ – by Yves Klein, Salvador Dalí

and Andy Warhol – next to a

Roman statuette. Can you say something about the rationale?

CL: It appears that, however unwittingly, I

was at the forefront of a trend. I’ve been connected with the twentieth and

twenty-first-century art market for some time – not least through my

partnership in Vigo Gallery in London. The idea for those juxtapositions really

came from when I was buying antiquities and noticed so many classically

inspired artworks along the way. I started actively looking for pieces

with interesting, classical themes – pieces that would encourage visitors who

were interested in the contemporary as well as in the ancient.

MS: So that’s how the collection got its

broad ‘classical’ remit?

CL: Despite the eclecticism of the

collection, I wanted to make sure the museum had a coherence – above all, that

it would tell a story for visitors. At the same time, it’s absolutely

astounding how many artists had a classical period in their work, emulating

ancient works, drawing pieces as part of their training, responding to them. The

more I collected, the more I realised the interconnection. I can’t think of

anywhere else in the world that demonstrates the point better than Mougins.

MS: Among your many current projects is the

exhibition you sponsored at King’s College London, dedicated to The

Classical Now – part of a larger project on ‘Modern

Classicisms’, which explores the interface between ancient visual

culture and modern and contemporary art. Why do you think this project is important?

CL: The aim here – and it’s very much

aligned with our work at MACM – is about challenging how people look at

antiquities. When they’re displayed in museums, ancient artefacts are usually

presented as pieces of history rather than as artworks: their significance is

often presented in terms of how bewilderingly old they are. But clearly, over

the years – including in modern times – artists saw things quite differently: ancient

artefacts provided materials for artists to study, emulate, respond to and challenge.

What appealed to me about this project is the way in which it encourages public

audiences to look to antiquities through the eyes of modern and

contemporary artists: that’s why The

Classical Now has had such traction, in my view – it’s engaging new

audiences, and across traditional divides of ‘classics’ and ‘art history’.

MS: Let me end by asking you about your

future collecting plans – both for MACM, and for your own extended collection.

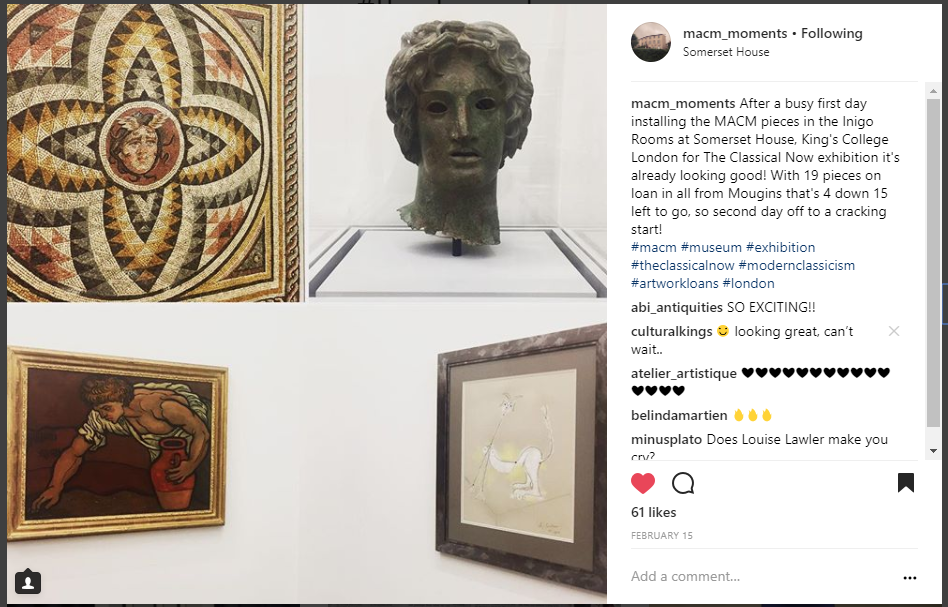

CL: MACM has become a living museum: local

members of the public want to see new things, so there have to be some changes

in the permanent displays. At the same time, it’s now become extremely

difficult to buy antiquities with decent provenance – something that has always

been central to my own collection. For many years I’ve wanted clearly defined

provenance prior to 1970 (something which Sotheby’s also requires for its

antiquities auctions), although now I’m really looking much further back than

that – normally to the early twentieth century for me to even look at a piece.

Partly for that reason, and in part for others, I’ve been collecting more and

more works by twentieth- and twenty-first century artists. As the collection

grows, MACM is prioritising loans of objects around the world, which in turn

allows space for temporary installations: a case in point is our current Léo

Caillard exhibition, Past

is Present, which forms the partner-show to The Classical Now in London. This interview is extracted from an interview

for Sotherby’s in London. Want to know

more about Chris Levett and his collection? We have uploaded the film of an interview

with the King’s team from November 2017 here.

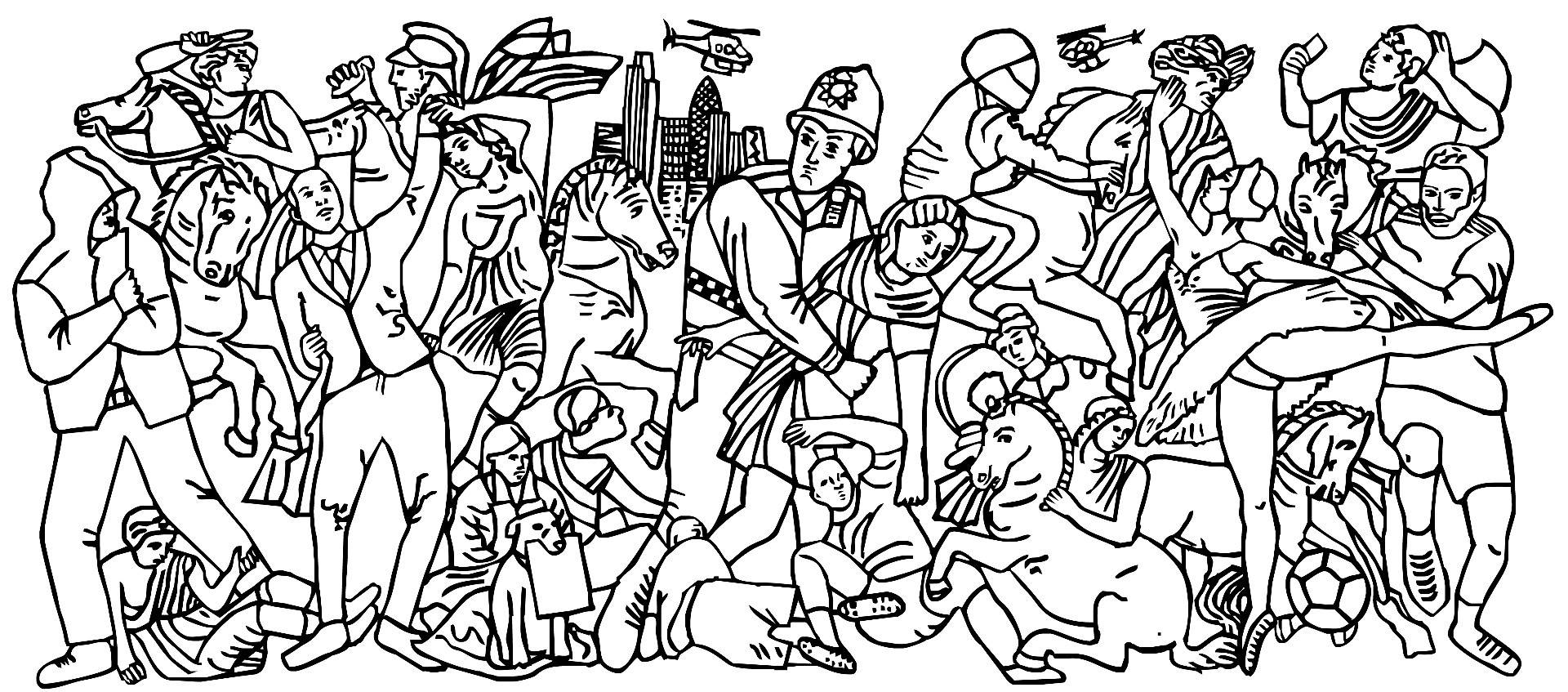

A MODERN DAY MINOTAUR

Artists Mary Reid Kelley (b. 1979) and Patrick

Kelley (b.1969) discuss with us ancient Graeco-Roman objects, themes

and myths – and how they have helped to inspire their own modern-day films. The

artists work in collaboration to create video works that combine painting,

performance and poetry; their films tell surreal stories inspired by history

and mythology. Played by Mary Reid Kelley, the multifarious characters speak in

poetic verse filled with wordplay and puns, and narrate stories that imagine

unrecorded histories. From November 2017 to March 2018, Tate Liverpool

presented the artists’ first solo exhibition in a UK museum, and Swinburne’s

Pasiphae (2014) was featured in our 2018 exhibition on The Classical Now. Mary Reid Kelley is a 2016 MacArthur Fellow and

received the Baloise Art Award at Art Basel in 2016.

James Cahill spoke with the two artists in connection with our

‘Modern Classicisms’ project at King’s.

JC [James Cahill]:

I’d

like to ask you how the idea for the trilogy of films

about the Minotaur came about – and why you decided to focus on the figure in

your three films (2013–2015):

Priapus Agonistes (2013), Swinburne’s Pasiphae (2014) and The Thong of Dionysus (2015).

MRK [Mary Reid Kelley]: We had the idea of

doing something with an ancient theme after living at the American Academy in

Rome for a year. It wasn’t a question of wanting to do something thematically classical

so much as the experience of living in Rome and recognising the historical

process of the deconstruction and reconstruction of the city through spolia –the use of discarded and recycled elements. Ancient materials

might be recycled into a medieval church, or ancient marbles cut up and used in

mosaic floors. Before going to Rome we had done historically themed works: we

did four films set in the First World War, and one in mid-nineteenth century

Paris. But it was living in Rome that gave us an idea of putting things from

different times, cheek-by-jowl with each other...

For

a while I’d been identifying the way that I write – with all the puns and

wordplay and rhymes – as ‘Dionysian’. So when we came to consider making three

films about the Minotaur, the myth was an extra impetus – an opportunity to

make something that was not just structurally or linguistically Dionysian, but

also thematically Dionysian. And in terms of how the Dionysian plays out in the

work, it’s something inescapable, like the sense of drunkenness: you can’t opt

out of being drunk once you are drunk, you just have to wait for it to wear

off. That’s one of the reasons we keep the films short. We want it to be an

intense and overwhelming feeling.

JC: The opposition between the

Apollonian and the Dionysian could be a useful way of thinking about your

embrace of the irrational and the taboo. One line that comes to mind when I

look at your work is Walter Pater’s reference to the ‘sharp bright edge of

Hellenic culture’, although he of course he had a particular vision of

antiquity. Your videos have a ‘sharp bright’ quality, but they’re very much the

opposite of what Pater was describing in relation to the classical statues.

PK [Patrick Kelley]: Mary generally

writes all the scripts, but the second film in the trilogy, Swinburne’s Pasiphae (2014), was drawn entirely

from a pre-existing text, a fragmentary poem by Charles Algernon Swinburne.

It’s Swinburne’s story of Pasiphae and describes the moment of Daedalus

building the cow for Pasiphae so that she can fulfil her desire for the bull. It’s

about Daedalus’s own ego and desire in creating the cow. We made our version of

Swinburne’s poem, using his text, word for word.

MRK: One of the interesting things about

working from a mythological basis, rather than making a historically based film,

is that while for a historical film you read memoirs and use photographs, with

mythology, you’re basing your work on other artistic interpretations – in this case,

Swinburne’s, but also those of artists like Picasso, Man Ray, Salvador Dalí and

other mid-century artists for whom mythology was really pertinent…

JC: What bearing do you

feel the Minotaur story has on the present day? Do its elements of subversion,

transgression, creative genius or bestial coupling have an enduring relevance?

MRK: I think all those

elements you listed still come into play in contemporary culture. The only one

that seems archaic is the bestial coupling, which serves as a nice marker in

the drift of taste in metaphor from ancient times to now. Of course, it’s not

just taste that’s intervened; it’s science, Darwin, genetics. But the

acquisition of this knowledge hasn’t made us very much better at tolerating

difference, which is what the Minotaur represents. The Minotaur is the ultimate

unwanted being…

JC: Art historically, there are lots of

different voices being brought into the mix besides your own, and in that sense

it becomes a kind of Modernist poem. I can’t help thinking of the dilution of

the self into the chorus of voices. And ‘chorus’ is a word that I think of in

relation to the work. When I hear your voice over the top of each video, Mary,

it reminds me of the chorus of Greek tragedy.

MRK: Yes, in the first film, Priapus Agonistes, there is a chorus

which reinforces the story. That was part of the classical theme – working with

ideas of the mask, the chorus and the verse play. I was very much inspired by

Eliot’s ‘Sweeney’ poems, in which Sweeney was inspired, I guess, by a bartender

that Eliot knew. And my character of Priapus was based on my first boyfriend from

when I was in high school.

The

thing that I think is really strange about the Minotaur story and other Greek

myths, is that it is very difficult for us to deal with is the idea of fate, of

being stuck in something against your own choosing. That was the Greek way of

explaining bad things: it was because the gods had thrown bolt at you or had

you on their blacklist. We’ve grown a counter-mythology to that, saying that we

can ‘bootstrap’ our way out of bad situations, to use American terminology. That

idea of fate is one part of Greek thought that has not come along with everything

else that we readily claim as our heritage from the ancient world.

A full version of this interview can be

read in the catalogue accompanying The Classical

Now, published in February 2018.Want to find out more? We have uploaded a more

detailed interview with the artists here.

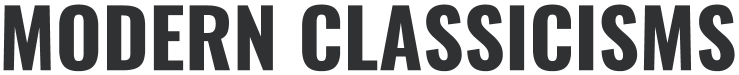

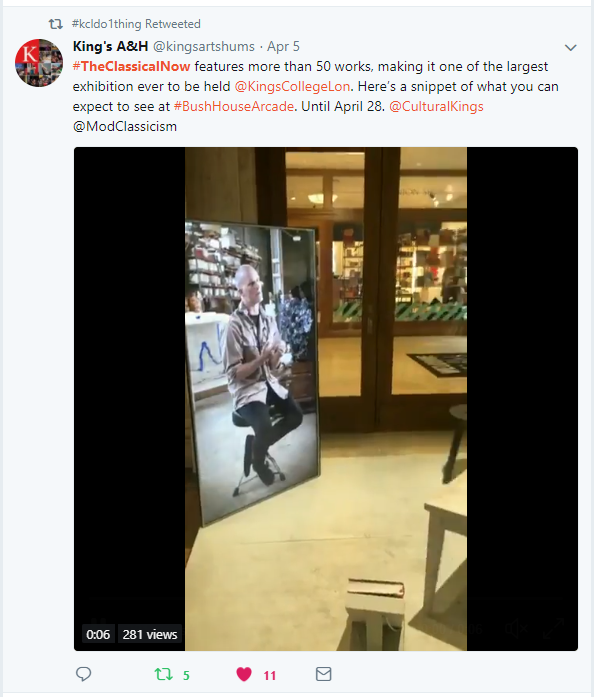

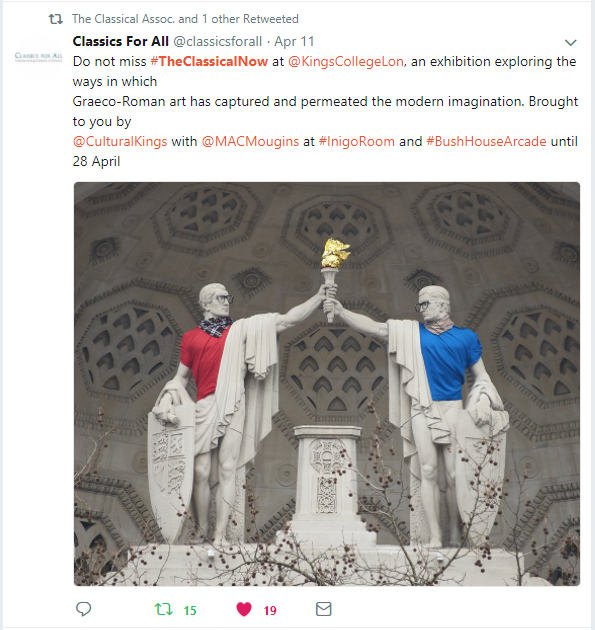

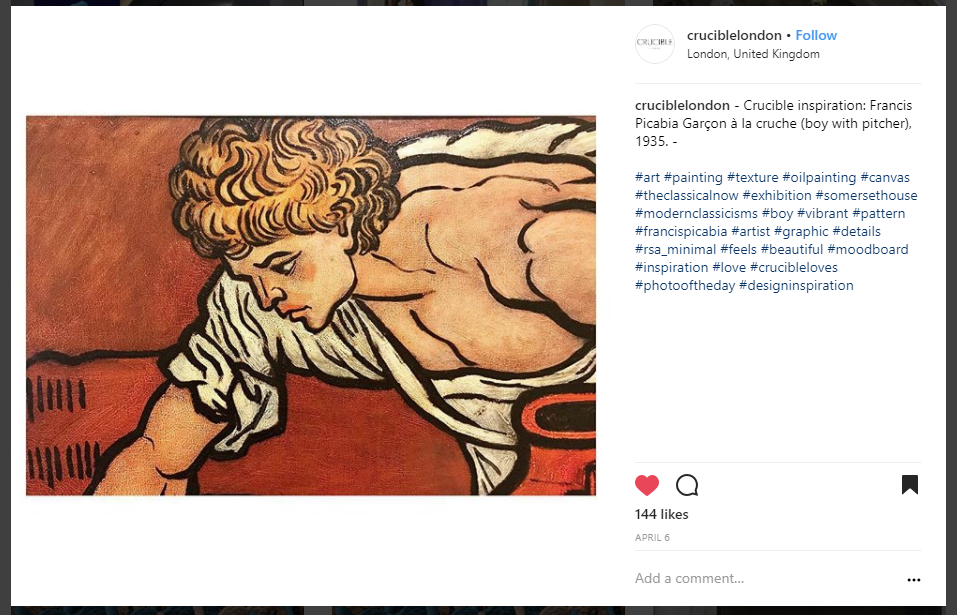

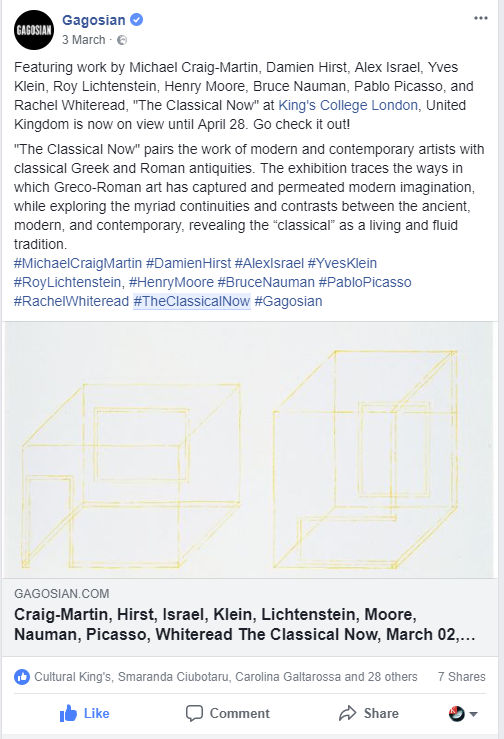

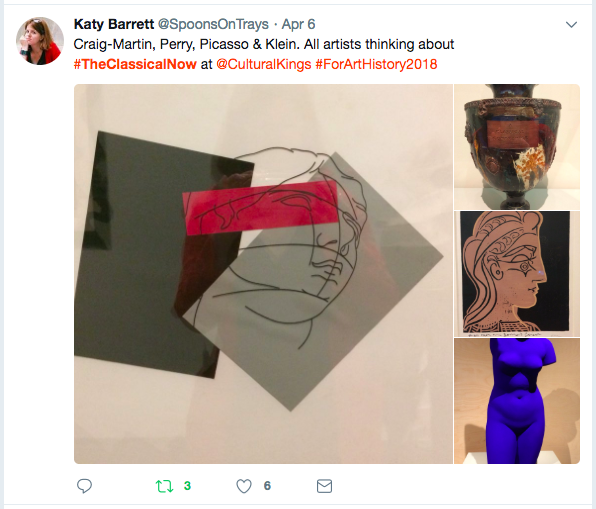

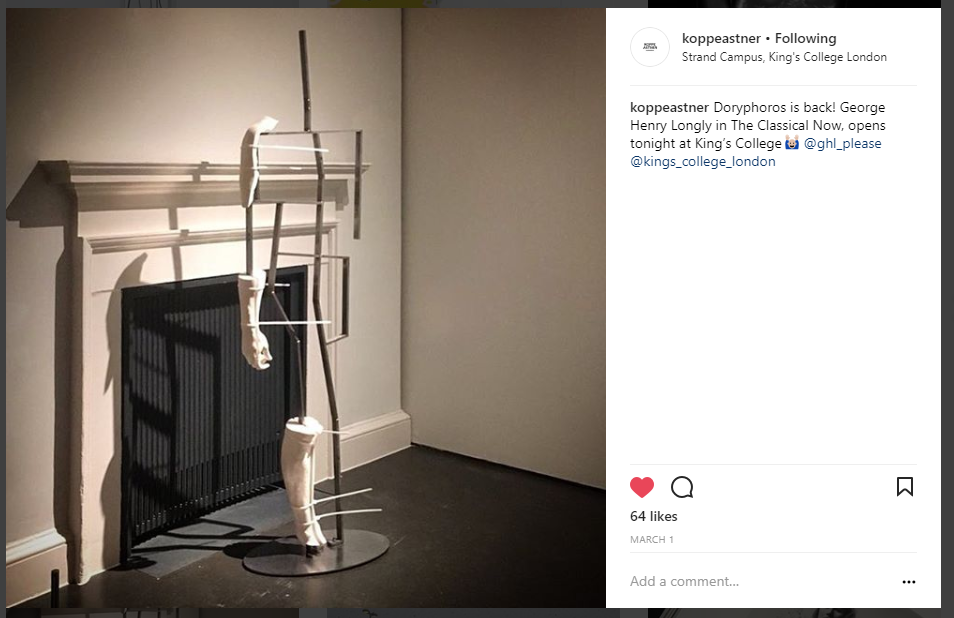

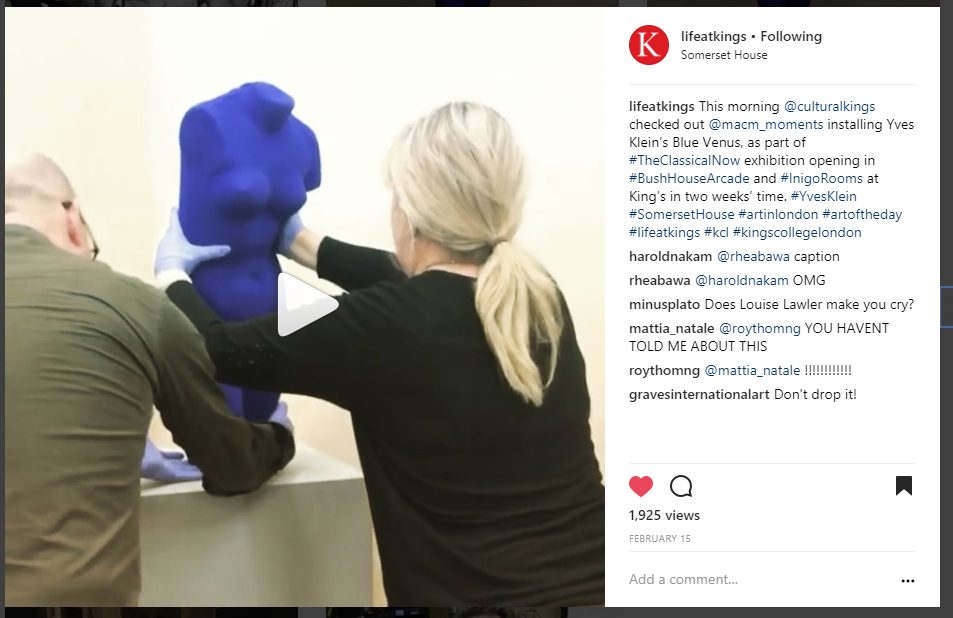

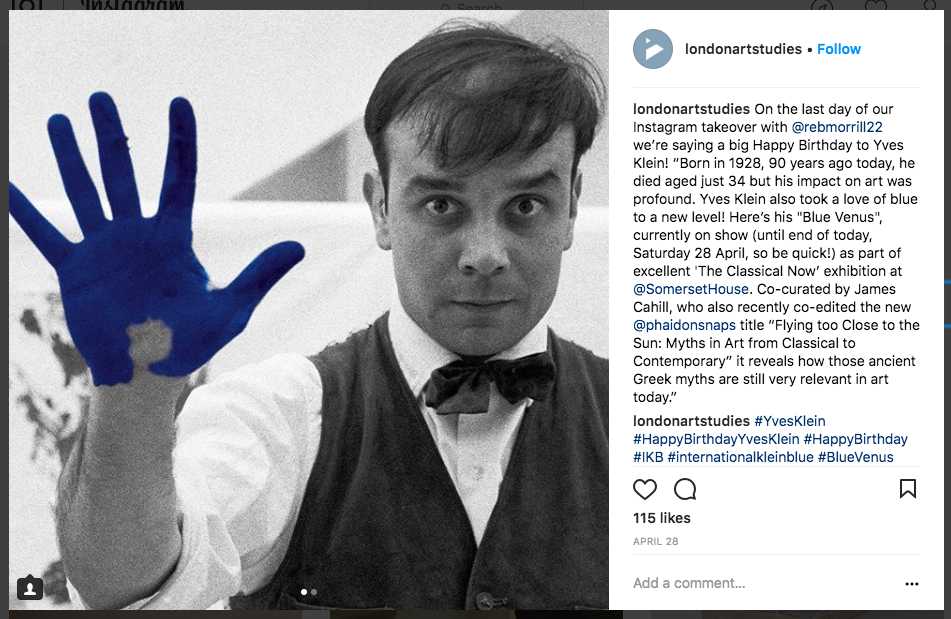

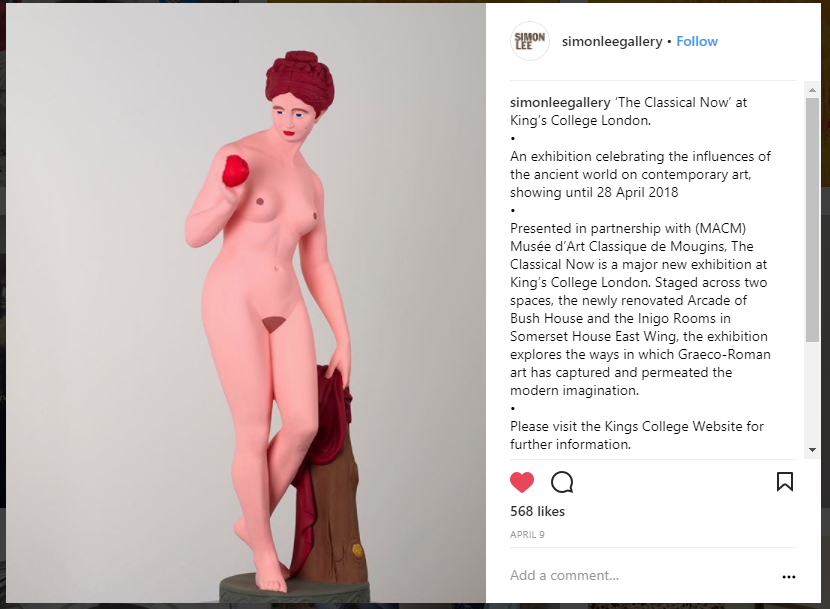

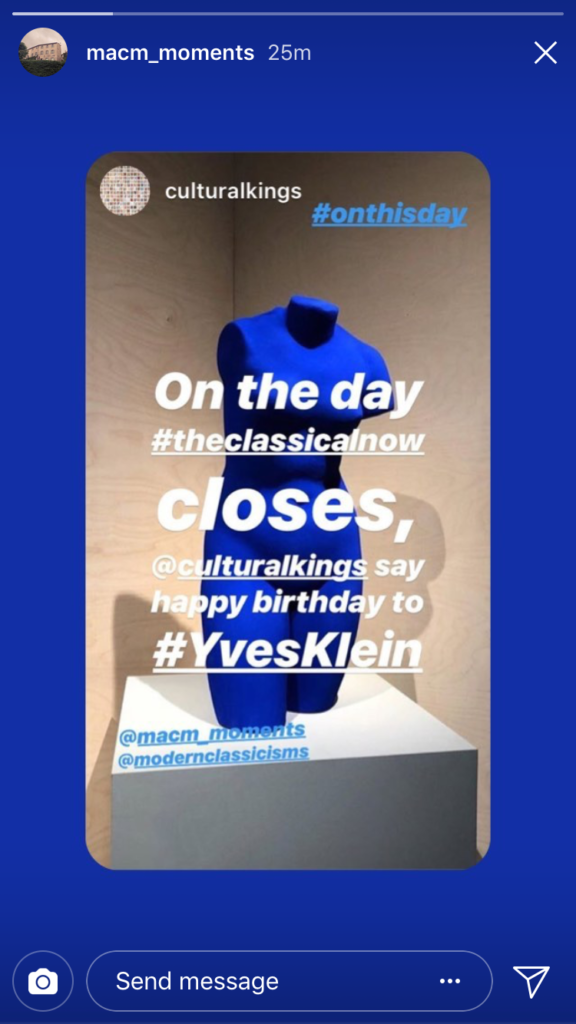

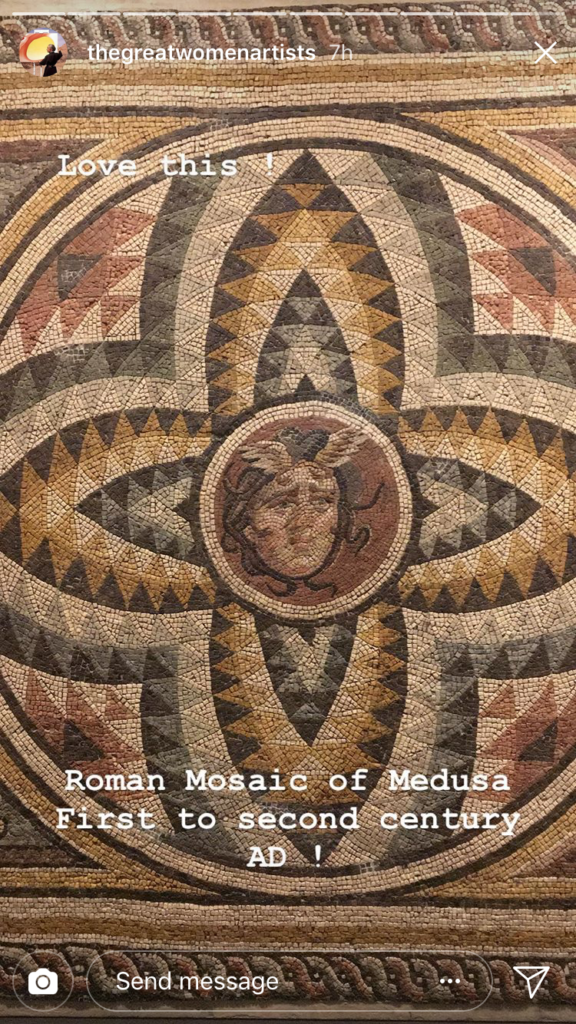

SOCIAL MEDIA

In case you missed them, here are some of our favourite social media responses to The Classical Now.

A short blog: we hope the responses speak for themselves….

A PERMANENT HOME FOR COMPETITION ENTRIES

A permanent home for competition entries

We’re pleased to announce that a selection of artworks that were originally entered in the Modern Classicisms competition are to be given a new home: they will be displayed in the Department of Classics at King’s College London. Thanks to the generosity of the Jamie Rumble Memorial Fund at King’s, some ten works by students and staff at King’s and the Courtauld have been purchased for permanent display. We hope to have the works installed by the end of 2018.

A CONTINUING PROGRAMME...

A continuing programme…

While lots of publicity has understandably focused on the exhibition, The Classical Now has also been accompanied by a major programme of cultural activities, designed to complement the show. We’ve had a weekend at the Royal Academy, a lecture by Mary Beard, an experimental ‘occasion’ and discussion hosted by artist Isabel Lewis, and a wonderful sound installation in the Strand ‘Roman baths’ by Gen Doy. For three days, from 5–7 April 2018, King’s College London and The Courtauld Institute of Art also co-hosted the Annual Conference of the Association for Art History, which brought nearly 1,000 delegates to the Strand – not just art historians, but also artists, curators and heritage professionals. The Classical Now and other activities related to the Modern Classicisms project loomed large in the programme.

Even though the exhibition itself has come to a close, the programme of cultural activities related to the project continues apace. We were delighted, for example, that Modern Classicisms was included in the wonderful ‘Art History: Undisciplined’ event organised by the Courtauld Institute of Art on 19–20 June 2018: a video of the relevant session can be found here.

RODIN'S 'MODERN CLASSICISMS'

Rodin’s ‘Modern Classicisms’

As one exhibition closes, another always opens. Although we were very sad that The Classical Now came to an end in late April 2018, what better time for the British Museum to launch their show on Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece. Rodin lived from 1840–1918, and the exhibition explores his intense and multiple engagements with ancient Greek sculpture (not least objects in the British Museum itself). Over the last year, the Modern Classicisms team at King’s has worked closely with our friends at the British Museum, and we were delighted to exhibit a wonderful statue of Venus from the museum in the show related to the project. The Rodin exhibition runs until the 29th July 2018, and we’re delighted to see so many points of intersection with our research project here at King’s.

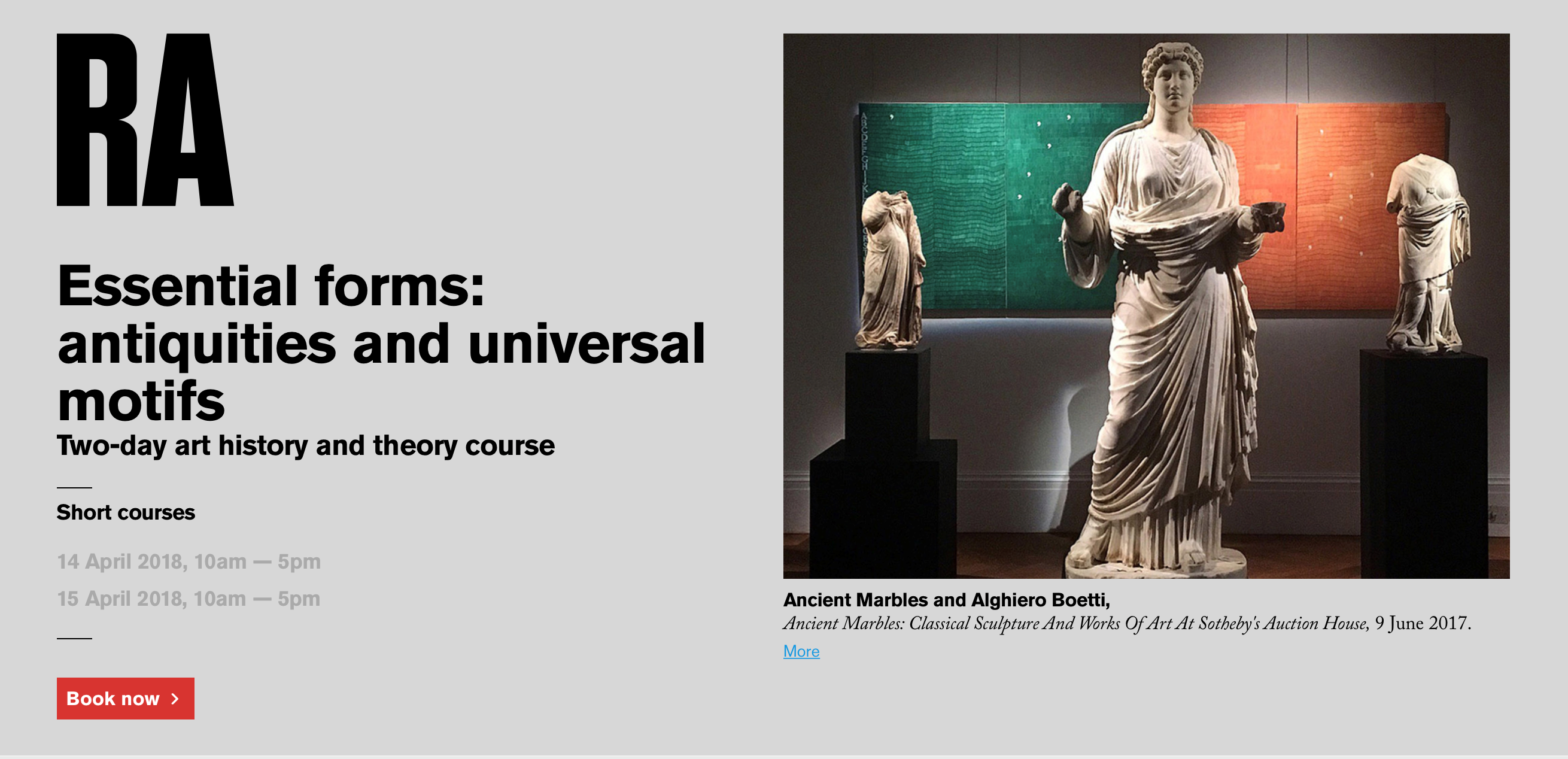

MODERN CLASSICISMS AT THE ROYAL ACADEMY

Modern Classicisms at the Royal Academy

The Modern Classicisms team was delighted, on 14–15 April 2018, to team up with the Royal Academy of Arts as part of a special weekend dedicated to Essential Forms: Antiquities and Universal Motifs. Housed in the ‘Life Room’ at the Royal Academy, and led by the indefatigable and hugely engaging Judith Nugée, participants discussed ‘the fascinating world of antiquities and the ancient arts – with a view to the timeless forms, ideas and universal motifs that are so influential across the arts and culture up to the present day’.

One of the particularly special things about the Royal Academy weekend was the opportunity to be in the ‘Life Room’ itself. Casts of classical statues are to be seen everywhere one looks, and originally the room was designed as a space for life-drawing classes.

It was also great to tie up our university research-project with the work of the Royal Academy itself. The President of the Royal Academy, Christopher Le Brun, has hugely enriched our Modern Classicisms work (you can watch the talk that he gave at King’s here, as well as his soundbites to a project video here). We also featured a painting and two sculptures by the artist in The Classical Now exhibition: although the show has now closed, you can read about Le Brun’s work in book that accompanies it.

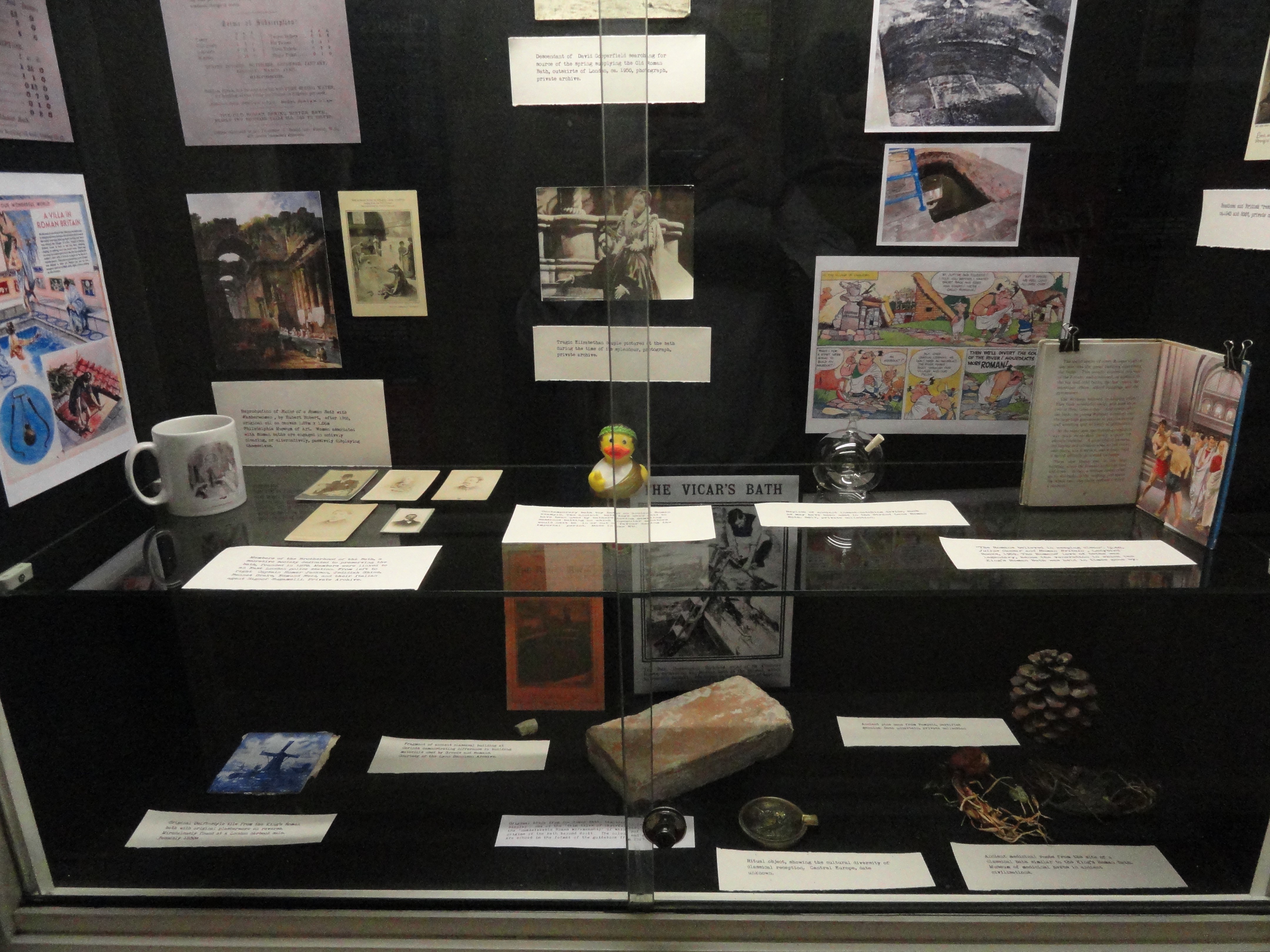

SOUNDING IMAGINED PASTS IN THE STRAND LANE 'ROMAN' BATH

Prof. Michael Trapp and Dr Gen Doy tell us about their ‘King’s Artists’ project, and its connections with Modern Classicisms and The Classical Now exhibition…

“‘Layers & Echoes’, the King’s Artists project affiliated to Modern Classicisms, is now nearing conclusion. Over the last eleven months, the Strand Lane ‘Roman’ Bath has seen a spoof exhibition, audio installations, live song, experiments with water sounds, and ventures in well-dressing, all masterminded by Gen Doy to tease out the layers of association and historical fantasy that have built up around this supposed survival of Roman antiquity into the modern world.

A special highlight were the video and sound installations in the Bath last April (coinciding with The Classical Now exhibition, as well as the Festival of the Association for Art History). Under the titles Wholly Water and Mare Nostrum, Gen and collaborating artist Lynn Dennison opened up the acoustic and atmospheric properties of the space and its imaginative relationship to the enduring lure of the classical. ‘Beautiful’, ‘thought-provoking’, ‘intriguing and profound’, and ‘lovely, especially the monstrous fish’, were some comments left by visitors.

But it’s not over just yet. An exhibition of works by all of this year’s crop of King’s Artists, which opens at Bush House on 23 October and runs until 15 December, will include art from the Bath residency re-worked for a gallery context. Michael Trapp will represent the Bath team at a panel discussion at Bush House on the evening of 12 November. Gen and Michael also invite you all to an ‘event’ in the Bath on 26 November from 5.30-7 pm at the Bath in Strand Lane, with a dark but not gloomy show of images linked, sometimes rather loosely, to the King’s Bath and other classical bathing imaginings. See you there!”

Further information will be published on the King’s Culture website.

Please send email enquiries to Michael Trapp directly.

Photos: Lynn Dennison, Rosanna McNamara & Michael Trapp

A BLOG ON BLOGS...

A blog on blogs…

It’s easy to think that, once an exhibition has opened its doors, the hard work must be over. In some ways that’s true. But no sooner was everything installed for The Classical Now than plans were under way for objects to be shipped back across the UK, Europe and internationally…

Another – rather more fun – labour lies in keeping tracking of public responses. In the case of the exhibition to the Modern Classicisms project, we’ve attracted media coverage from across the world – not just in the UK, but also in (for example) Germany, the States and France. Coverage rolled continually, as when we received a nice Guardian plug (‘What to see in the UK this week’) mid-way through the run.

Other sorts of responses are harder to keep on top of. We had the benefit of lots of social media discussions, for example – but if visitors didn’t use the #theclassicalnow hashtag on Instagram or Twitter, their responses risked getting lost in the ether.

It was fun to see some of our exhibited artists discuss the exhibition on their websites, among them Damien Hirst and Marc Quinn. But another hugely important medium is the blog: we were delighted to read responses by academic bloggers like Mary Beard and Peter Lowe. At the same time, it is exciting to see wider engagements with our work – as with a nice Sotheby’s blog, for example, or a thought-proving blog about ‘what museums are for’ (where our exhibition was praised for getting visitors ‘to look beyond the objects in the room, to evaluate not just visual material but arguments and assumptions—whether in their own minds, the museum, or western tradition at large’). Some blogs were from particular disciplinary interests – like a nice piece by ‘Ian the Architect’. Other bloggers promise their public that every time they ‘come across something interesting, you will be the first to know’, as with a blog by Jude’s London eye.

The inevitable challenge, of course, lies in keeping a record of all this feedback. If you’ve blogged or posted about the exhibition, please do let us know by emailing info@modernclassicms.com. And if you missed the exhibition, you can still learn more about it via internet archives – including this nice radio feature from March 2018.

‘ON SYMPATHY’

‘ON SYMPATHY’: A ONE-OFF OCCASION HOSTED AS PART OF THE CLASSICAL NOW EXHIBITION

We are delighted that King’s College London and The Courtauld will be hosting the 2018 Association for Art History Annual Conference; as a special, one-off event, the Conference this year will also include a Friday lunchtime Festival, curated by Abigail Walker (student ambassador on ‘Modern Classicisms’).

The Festival is a way to start thinking differently. It will both celebrate and challenge the current forms of art historical research, study and engagement. Composed of various events, workshops and visits, the Festival looks to complement the Annual Conference proceedings and themes in a discursive and exploratory environment. It investigates topics such as access to art history and to knowledge of the subject; it will also explore alternative ways in which art historical work can be interpreted. It offers the opportunity to experience art, music and debate in an informal environment.

In collaboration with our major exhibition, The Classical Now, artist Isabel Lewis will be hosting an occasion in the Bush House Arcade. The event will form part of the Conference Festival, and this particular component will be free to the public. The event is called ‘On sympathy’, and has been organised together with Michael Squire and Brooke Holmes.

The organisers write: ‘We tend to think of sympathy as a relation between persons. But in the fourth century BC, Greek philosophers started to talk about sympathy as something diffused throughout the world, affecting human and non-human bodies alike. What is at stake in expanding our own concepts of sympathy today, beyond communities imagined in human terms? In doing so, what kind of relation do we open up with the past and those long dead? How do these experiments in sympathy affect, in turn, how we come to be with one another – our living in shared space? And in what ways might these questions help us, according to the rallying cry of the Association’s 2018 Annual Meeting, to “look out!”?’

Lewis’ occasions are immersive, multi-sensory, ecological experiments in the cultivation of conditions for working through, collectively, the questions of living well and living together.

The event will be open to the public as well as delegates of the Conference; participants will be free to come and go as they please. Why not combine your visit to our exhibition with this unique opportunity to experience the work of Isabel Lewis? And if you are attending the Association for Art History Conference, there is also a chance for a curator-led tour of The Classical Now during the lunch-break on Thursday 5 April.

The 2018 Annual Conference Festival will take place on Friday 6 April, 12.30-3.00. To see all events organised by the King’s Faculty of Arts & Humanities to celebrate The Classical Now, click here.